Originally published by Huffington Post Quebec, May 20, 2014

Article by Michelle Whiteman

You may visit the original article here.

Alors que se tenait la Conférence mondiale des Nations Unies de 2001 contre le racisme à Durban en Afrique du Sud et où l’on a entendu le slogan « un Juif , une balle », une campagne fut lancée pour isoler Israël. Elle avait pour but de délégitimer Israël en utilisant le modèle réussi de l’isolement international du régime de l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud. Ce qu’on ne pouvait pas obtenir par la vérité, on essaierait de l’obtenir par la propagande. La discrimination effroyable qui s’exprima à Durban poussa le sous-ministre des Affaires étrangères de l’Afrique du Sud , Aziz Pahad, à émettre une déclaration dans laquelle il déplorait les «événements honteux » qui avaient eu lieu et le « détournement » de la conférence en « un événement antisémite ». Comme Irwin Cotler l’a remarqué, la conférence, qui devait mettre fin au racisme, était elle-même l’expression du racisme. Dix pays occidentaux ont boycotté Durban II.

Malheureusement , les échos honteux de la conférence de Durban se répercutent encore aujourd’hui dans certains milieux où le mot «apartheid» est utilisé pour délégitimer l’État juif . Alors que la plupart des grands médias évitent généralement de relayer l’analogie diffamatoire entre Israël et l’apartheid et permettent d’effectuer des corrections, il existe des exceptions. Notre demande de correction concernant la récente comparaison faite par la chroniqueuaw de La Presse Agnès Gruda entre Israël et l’apartheid a été rejetée par les rédacteurs de La Presse. Voilà ce qu’il en est des principes journalistiques d’exactitude et d’équité.

Le terme apartheid est défini exclusivement dans un contexte de discrimination raciale et implique une intention de discriminer sur la base de la race (Statuts de Rome). Le mot apartheid a une signification particulière. Il n’existe pas de « sens général» au terme «apartheid», ainsi que Mme Gruda le soutient. L’apartheid est soit une discrimination fondée sur la race ou ça ne l’est pas. Si ça ne l’est pas, il ne s’agit ni de racisme ni d’apartheid et l’utilisation du terme est donc inflammatoire et diffamatoire.

Cela résume l’article de Mme Gruda qui affirme à tort que «les colons juifs de Cisjordanie, eux, circulent sur des routes séparées». Le message de l’apartheid est clair, mais faux. Parmi les milliers de kilomètres de routes et d’autoroutes de Cisjordanie empruntées à la fois par les Juifs et par les Palestiniens, une poignée de routes sont considérées comme étant trop dangereuses pour les Israéliens. Ces routes sont situées dans des zones qui ont été la cible d’attaques sanglantes par des cellules terroristes palestiniennes de Cisjordanie, qui visent les véhicules avec des plaques israéliennes. En effet, au cours de la deuxième intifada, des milliers d’Israéliens ont été tués dans des attaques terroristes, et les problèmes demeurant encore aujourd’hui. C’est ainsi qu’en avril, un Israelien a été tué lorsque des terroristes palestiniens ont ouvert le feu sur des véhicules israéliens en Cisjordanie.

Ce petit nombre de routes n’est pas exclusivement réservé aux juifs, comme Mme Gruda le prétend, mais a toutes les religions et ethnies – les arabes israéliens, Bahai, chrétiens, druzes, circassiens et toutes autres qui circulent en voiture avec une plaque d’immatriculation israélienne. Cela démontre assez clairement qu’il n’y a aucune ségrégation, ni religieuse ni raciale.

Pour Mme Gruda, Israël pratique « l’apartheid » parce que les Palestiniens de Cisjordanie n’ont pas le droit de vote en Israël. Mme Gruda omet de mentionner que les Palestiniens de Cisjordanie ne sont pas citoyens israéliens. En prévision de l’échange de territoires contre la paix, Israël n’a jamais annexé la Cisjordanie.

De plus, de nombreux pays du monde qui ont annexé des territoires n’accordent pas de droit de vote à leurs résidents. Pourtant, ces pays ne sont pas accusés d’apartheid. Tel est par exemple le cas de Puerto Rico dont les habitants ne peuvent pas voter aux élections américaines. Le critère reconnu est celui de la nationalité (et non pas du territoire) et n’a rien avoir avec l’apartheid.

Avec une presse libre, des élections libres, la liberté religieuse, les droits complets pour les femmes et les minorités, la primauté du droit et un système judiciaire indépendant, Israël est une démocratie dynamique et progressive où les Arabes jouissent non seulement des mêmes droits que tous les autres citoyens israéliens mais occupent également des postes importants. Selon Salim Joubran, Israélien arabe et juge de la Cour suprême du pays, « Israël est un endroit ou règnent les règles de la diversité « . Richard Goldstone , ancien juge de la Cour constitutionnelle sud-africaine et chef de la mission d’enquête des Nations Unies sur la guerre de Gaza en 2008, a affirmé : « En Israël, il n’y a pas d’apartheid. Rien ne s’y approche de la définition de l’apartheid « . C’est ainsi que dans le cadre d’opérations militaires courageuses, le gouvernement israélien a sauvé presque la totalité de la communauté juive opprimée d’Éthiopie en les faisant venir en Israël où ils ont pu profiter pour la première fois de l’égalité et de la liberté.

Alors qu’Israël ne pratique pas la ségrégation ethnique ou religieuse ni dans son réseau routier ni autrement, il y existe effectivement des routes au Moyen-Orient qui sont ségréguées, par exemple en Arabie saoudite, ou certaines routes sont réservées seulement aux musulmans. Les Saoudiens pratiquent également l’apartheid fondé sur l’orientation sexuelle en emprisonnant et exécutant les homosexuels et lesbiennes. Des politiques discriminatoires sont également pratiquées en Jordanie où les Palestiniens n’ont pas le droit d’exercer certaines professions. À Gaza, le Hamas discrimine ouvertement les femmes, les homosexuels et les chrétiens et va bien au-delà de l’apartheid en affirmant officiellement son aspiration d’anéantir les Juifs à travers le monde. En Cisjordanie, le président palestinien Mahmoud Abbas a déclaré ouvertement qu’un futur État palestinien ne tolérera pas la présence de Juifs. En Iran, les homosexuels sont publiquement pendus a des grues. Dans pratiquement tous les pays du Moyen-Orient, la population chrétienne a chuté – à une exception près : en Israël, ou la population chrétienne a quadruplé.

En fin de compte, le silence face au véritable apartheid est peut-être la preuve la plus révélatrice de la malhonnêteté de la campagne qui est menée contre l’État d’Israël. Il est regrettable que La Presse se joigne a cet effort.

VOIR AUSSI SUR LE HUFFPOST

In the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company founds Cape Colony, the first permanent European settler outpost in South Africa. Many of the locals are moved out of their land, while others are used for forced labor.

The 18th and 19th centuries see the expansion of European settlements on the continent, known as the “Scramble for Africa.” By the beginning of the 20th century, control over the southern part of Africa has fallen largely to the British, who hold two of the four divided colonies of South Africa. The other two colonies are controlled by the Boers, a Dutch-descendent subgroup of the Afrikaners.

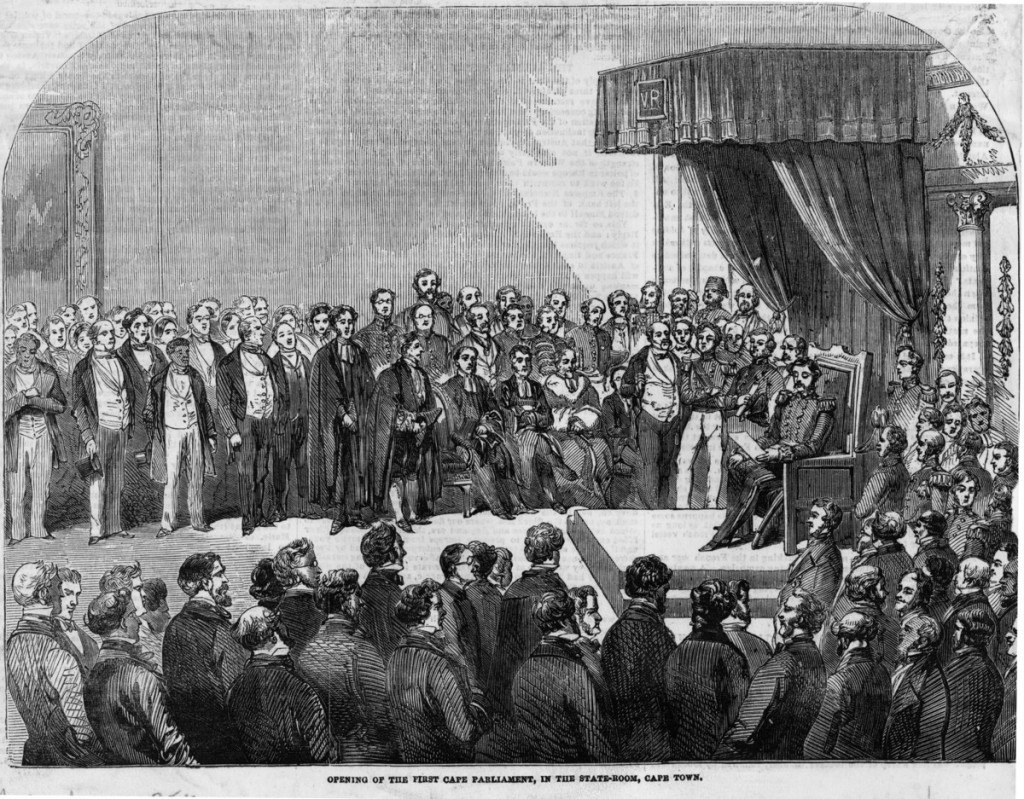

1st July 1854: Opening of the first Cape Parliament in the State Room, Cape Town. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A major driving force behind South African settlement is the discovery of diamond and gold reserves in the 19th century, particularly in Kimberley and the Transvaal.

Already resentful of the abolition of slavery by the British Parliament and its attempts to institute a more racially egalitarian society, 15,000 people of Dutch origin establish two independent republics: the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. When the British proposed a confederation of South African states in 1875, the Boers refused — first non-violently and then with force. The conflict results in two Anglo-Boer Wars. By the end of the second war in 1902, the two previously Boer colonies are under control of the British Empire, which now holds all four South African colonies. A sense of Afrikaner nationalism prevails among the defeated.

The Kimberley diamond mines in South Africa, to which thousands flocked in the 1870’s after the discovery of diamonds on the nearby De Beers farm. (Photo by Gray Marrets/Getty Images)

In May 1910, the four colonies are combined to form the Union of South Africa, the predecessor to the current Republic of South Africa. The Union functions as a self-governing dominion of the British Empire, with the new constitution placing political control in the hands of whites. Louis Botha is appointed prime minister of the Union after the elections of 1910.

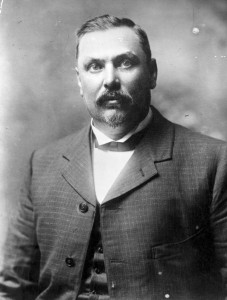

1907: Louis Botha (1862-1919) South African general in the Second Anglo-Boer War, and first prime minister of the Union of South Africa after its establishment in 1910. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The few rights guaranteed to black South Africans are eliminated in the new Union, as new laws seek to further entrench white power. Among these are poll taxes to restrict black voting rights and the 1913 Natives Land Act, which formally reserves a minuscule amount of land for black settlement. More than 90 percent of the country’s property is handed over to the white minority.

The Houses of Parliament in Cape Town, South Africa, circa 1910. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1912, the South African Native National Congress is founded with the goal of protecting the interests of both mixed-race and black South Africans. In 1923, the party is renamed the African National Congress (ANC).

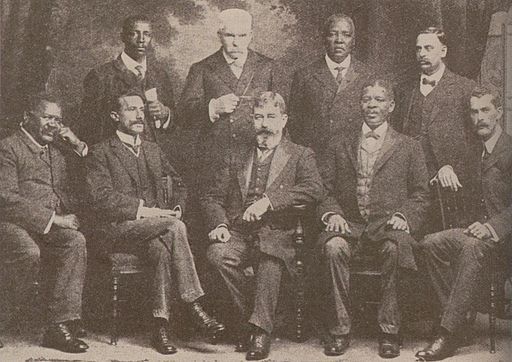

Delegation of prominent Cape Town politicians who oppose the racist provisions of the draft to form the Union of South Africa. (South African Library, Cape Town, Wikipedia)

The National Party (NP) is founded in 1914 by J. B. M. Hertzog, a former Boer general who promotes fierce nationalism. He aims to protect Afrikaner interests from British imperial control and preserve white interests from black South Africans.

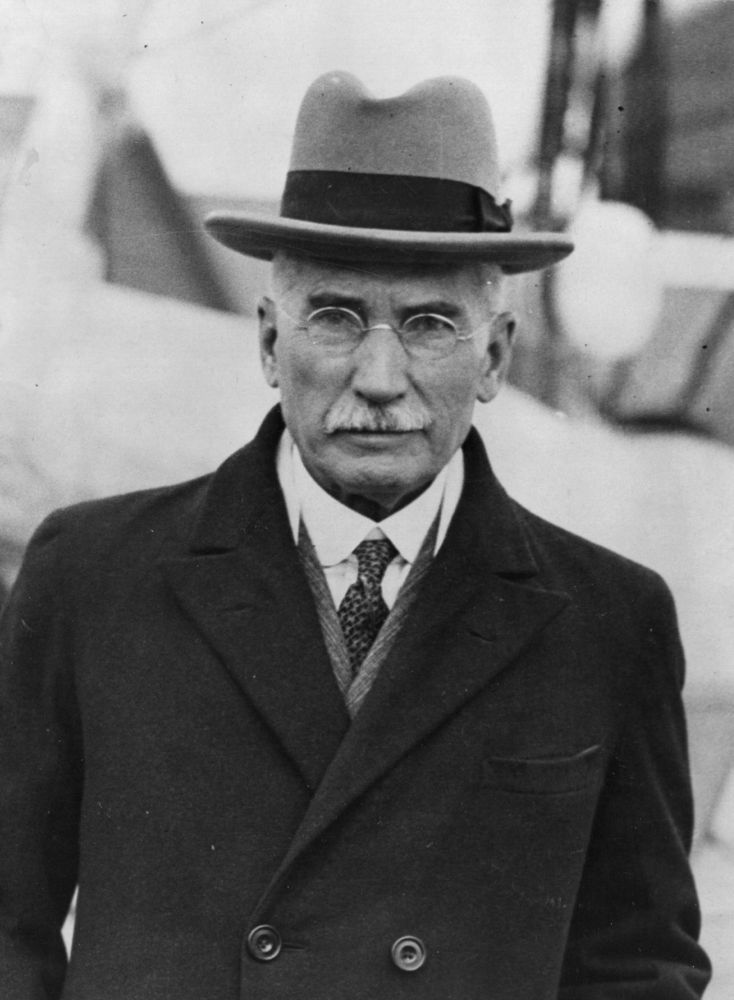

James Hertzog (1866-1942) the Afrikaaner South African soldier and statesman who founded the Nationalist Party in 1913 and later served as prime minister, circa 1920. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

On July 18, 1918, Rolihlahla Mandela is born into a royal family in the small village of Mvezo. His father is Chief Henry Mandela of the Thembu tribe.

The ‘Great Place’ palace at Mqhekezweni where former South African President Nelson Mandela was entrusted under the guardianship of Thembu regent, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, is pictured on April 5, 2013. Mandela was raised by Jongintaba and his wife Noengland alongside their son Justice and daughter Nomafuis at the Great Place. (CARL DE SOUZA/AFP/Getty Images)

Policies such as the Land Act serve to severely limit not only black ownership, but also the ability of native South Africans to receive education and independent income. Various laws reserve skilled jobs solely for white employees, relegating blacks to the cheap, unskilled labor force driving the white-controlled mining and farming industries. Blacks are only allowed on white land if they are employed by whites. By 1939, less than 30 percent of blacks are receiving formal education, while whites earn more than five times the wages of native South Africans.

3rd May 1939: A group of miners with safety lamps in the Robinson Deep Gold Mine at Kimberley, South Africa. (Photo by Reg Speller/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

The segregation of previous decades becomes even more structured in 1948, when the NP wins the all-white elections and passes a set of 317 laws that formally establishes institutional discrimination throughout South Africa. The policy is named Apartheid, which means “apartness” in Afrikaans.

South African politician Daniel Francois Malan, who led the Nationalist Party into government in 1948 and began instituting the white-supremacist doctrine of Apartheid as official policy. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The 1950 Population Registration Act requires all persons to be classified in three categories according to race: white, black, and “colored” (mixed-race). A fourth category, “Asian,” would later be added to include immigrants from India and Pakistan. The classification is based on subjective traits such as habits, education, appearance, and manner, and families are often split into different categories.

Picture released in January 1947 illustrating the Indian population living in South Africa. (AFP/Getty Images)

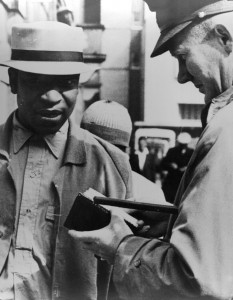

Throughout the 1950s, several laws restrict the day-to-day lives of blacks in all areas of life — from marriage to access to public space — as part of a system of “petty Apartheid.” In 1949, the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act outlaws interracial marriage. In 1950, the Group Areas Act restricts blacks from entering white areas without sufficient documentation, thus requiring blacks to carry “pass books” — essentially internal passports.

A policeman checks the identity card of a black citizen. Enforcement of the Pass Laws controlled the movement and employment of blacks. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

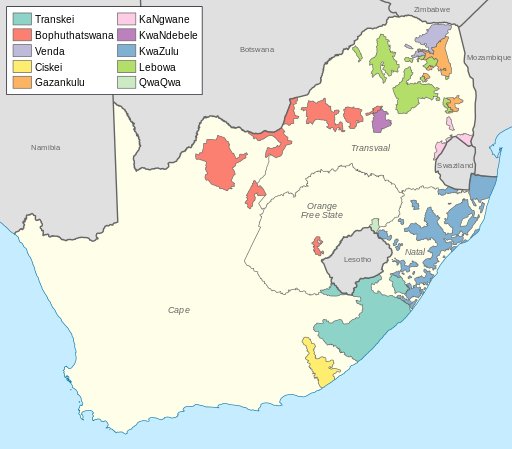

The 1951 Bantu Authorities Act, coupled with the 1959 Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act, creates 10 “homelands” for natives, known as Bantustans, each ruled by a body separate from the South African government. These laws are promoted by the new prime minster, Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, as part of a system of “separate development.” They create the legal basis for the deportation of blacks to one of these “homelands” for the purpose of denaturalizing native Africans, preventing them from forming a voting majority and thus removing them from national politics.

Between 1961 and 1994, more than 3.5 million black South Africans are deported to one of these Bantustans, where they live in poverty and hopelessness.

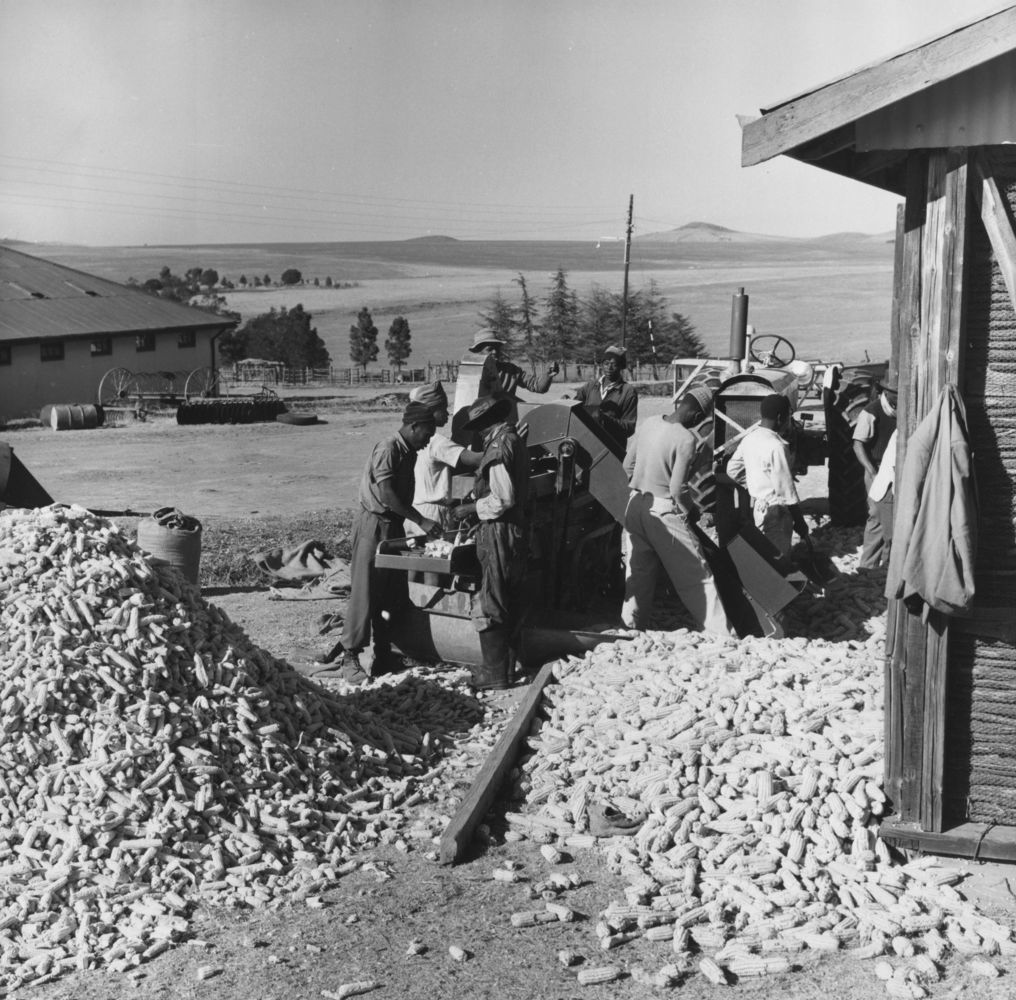

The 1953 Bantu Education Act applies Apartheid to the education system. It creates a separate Black Education Department tasked with forming a curriculum tailored to the “nature and requirements of the black people.” It is designed to teach native Africans to be “hewers of wood and drawers of water” and prevent them from learning skills used in more desirable jobs.

15th November 1961: Agricultural students grading maize at the School of Agriculture for Africans at Tsolo, Transkei. (Photo by Ron Stone/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Resistance to Apartheid is largely based in the nonviolent teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. In the 1952 Defiance Campaign, for example, Nelson Mandela and several other black South Africans burn their pass books in protest.

An unlocated photo taken in South Africa in the 1950s shows supporters of the African National Congress (ANC) gathering as part of a civil disobedience campaign to protest the apartheid regime of racial segregation. (AFP/Getty Images)

In 1960, police open fire on a large group of blacks associated with the Pan-African Congress (PAC), an offshoot of the ANC, who refuse to carry their pass books in protest. The government declares a state of emergency and bans both the ANC and the PAC. By the end of the Sharpeville Massacre, 69 people are left dead and 187 are wounded in a span of 156 days.

The aftermath of the massacre at Sharpeville, thirty miles from Johannesburg, in which more than fifty black South Africans lost their lives. Police opened fire on them during a demonstration against the rule which forces black citizens to carry passes. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

The bloodshed in Sharpeville convinces most anti-Apartheid leaders that their previous strategy of nonviolent, civil disobedience would not suffice, and both the ANC and the PAC establish military wings that pose no real threat the the government. Mandela is one of the founders of Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), the military wing of the ANC.

Former South African President Nelson Mandela’s room is seen in Liliesleaf farm on June 5, 2008 in the Liliesleaf Farm museum in the Rivonia area of Johannesburg. Liliesleaf Farm occupies a momentous place in South African history and socio-cultural evolution, as it was the site responsible for breaking the resounding political silence of the 1960s. Originally purchased in 1961 by the South African Communist Party, Liliesleaf farm is recognized by the ANC as the birthplace of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the military wing of the African National Congress. (GIANLUIGI GUERCIA/AFP/Getty Images)

In 1962, the United Nations establishes the Special Committee Against Apartheid to maintain international pressure against the racial injustice in the form of sanctions and public relations campaigns.

Protestors outside the hotel in Pretoria where Dag Hammarskjold, Secretary-General of the United Nations, is staying, 10th January 1961. Hammarskjold meets with South African prime minister Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd for talks on South Africa’s racial policies. (Photo by Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In August 1962, Mandela is arrested and charged with inciting workers to strike and leaving the country without a passport after a clandestine trip throughout Africa and to London to promote Umkhonto we Sizwe. He is sentenced to five years in prison.

Two years later, in 1964, Mandela is retried along with several of his associates and convicted of sabotage. He is sentenced to life in jail.

A file photo dated 1961 of African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela. (STF/AFP/Getty Images)

In 1968, medical student Steve Biko cofounds the South African Students Organisation (SASO) based on the philosophy of black consciousness, which encourages blacks to embrace their cultural identity and reject all notions of inferiority and foreign status in their own land.

Throughout the 1970s, the Black Consciousness Movement spreads across the country’s universities, with students forming a mass, grassroots resistance to Apartheid.

Steve Biko Memorial, East London, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (Getty)

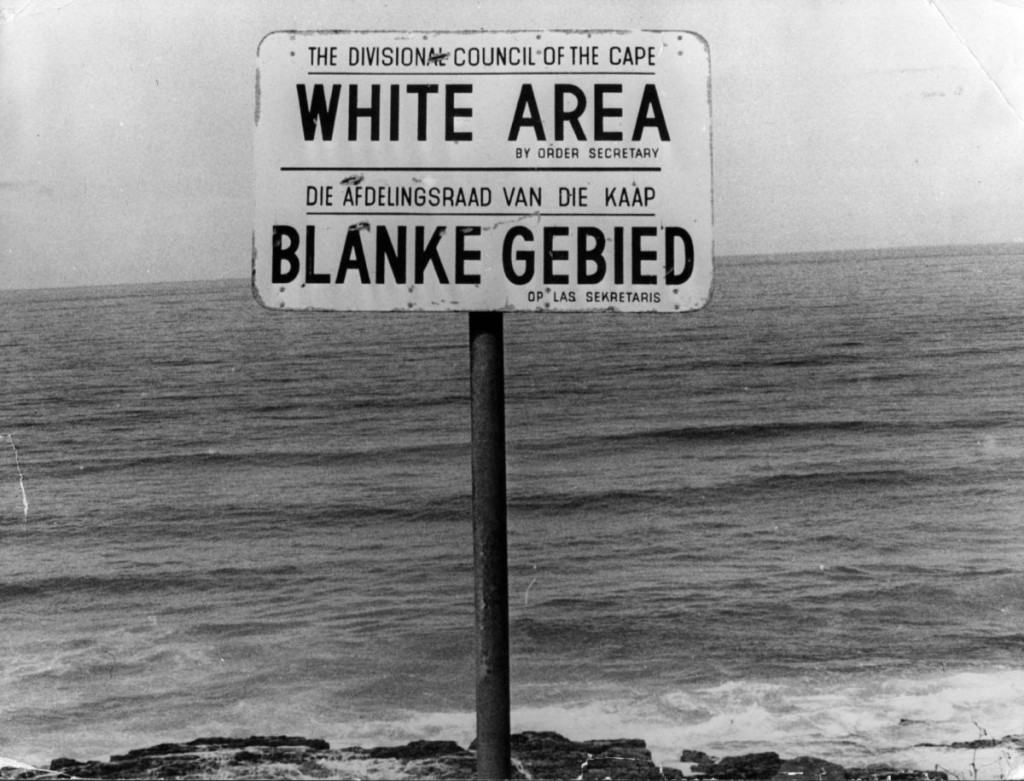

In 1970, the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act declares all native Africans to be citizens of one of the 10 “homelands,” rather than of South Africa itself. Between 1976 and 1981, eight million blacks are stripped of their South African citizenship.

An Apartheid notice on a beach near Capetown, denoting the area for whites only. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

On June 16, 1976, police meet thousands of students with violence as the students are marching peacefully to protest a new government mandate requiring the Afrikaans language to be taught alongside English in schools. The uprising spreads from Soweto to towns across South Africa over the following year.

While the government’s official death toll counts 176 dead in the Soweto Youth Uprising, further estimates put the casualties from the resulting aftermath as high as 700. The images of police brutality against peacefully demonstrating students further galvanize international outrage.

21st June 1976: A rioter in Soweto, South Africa. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

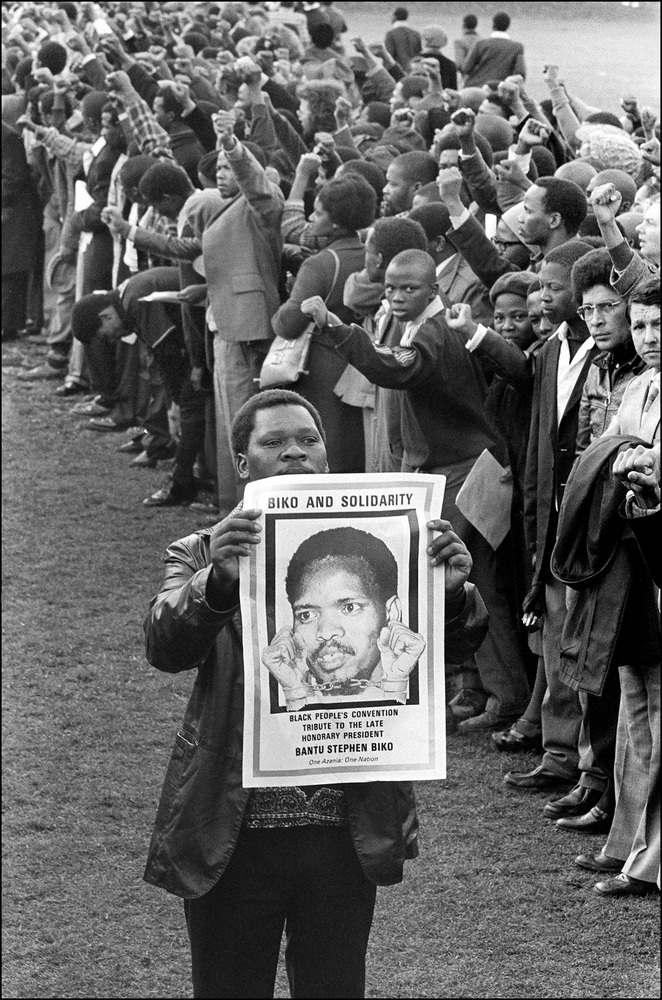

In September 1977, Steve Biko dies on the floor of his jail cell after being severely beaten by officers. Biko’s death propels him to martyrdom in the struggle for black nationalism.

Picture taken 03 October 1977 in King William’s Town of several anti-Apartheid militants attending the burial ceremony of Steve Biko. (STF/AFP/GettyImages)

Renewed international pressure places further strain on the national government. In November 1977, the UN Security Council votes to place a mandatory embargo on the sale of arms to South Africa.

29th June 1970: A London policeman bars the way to Downing Street to a group of anti-Apartheid demonstrators protesting against the supply of arms to South Africa. (Photo by Frank Barratt/Keystone/Getty Images)

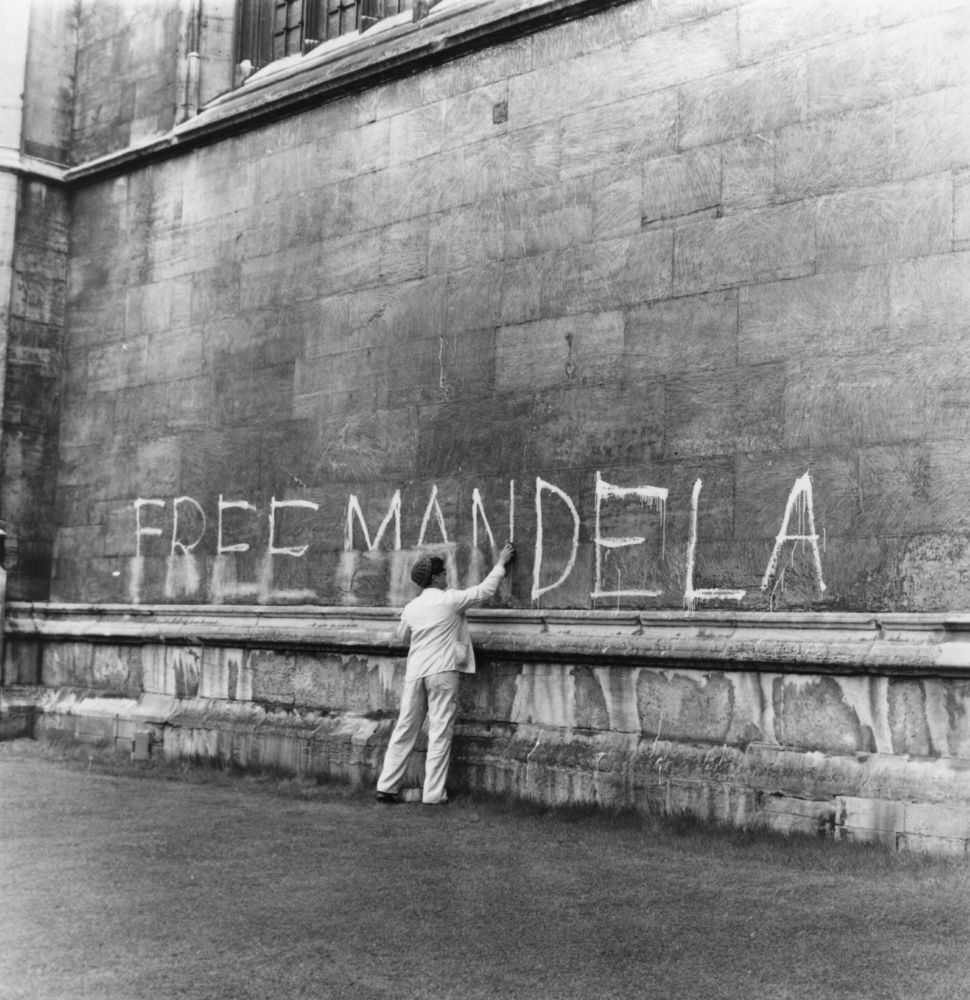

In June 1980, the UN Security Council officially condemns police violence in South Africa, calling for the government to end Apartheid, grant equal rights to all citizens, and release all political prisoners, including Mandela.

A man washing a ‘Free Mandela’ slogan off the side of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge. (Photo by Peter Dunne/Getty Images)

The South African regime faces significant internal pressure throughout the 1980s. Prime Minister P. W. Botha attempts to appease citizens by forming a Tricameral Parliament that includes colored (mixed-race) and Indian legislatures, but still excludes Africans. The move is purely for show, as the white legislature maintains all political power.

A policeman arrests two Indian men of South Africa, on November 14, 1983 during a demonstration against Apartheid outside Durban city Hall. (Paul Weinberg/AFP/Getty Images)

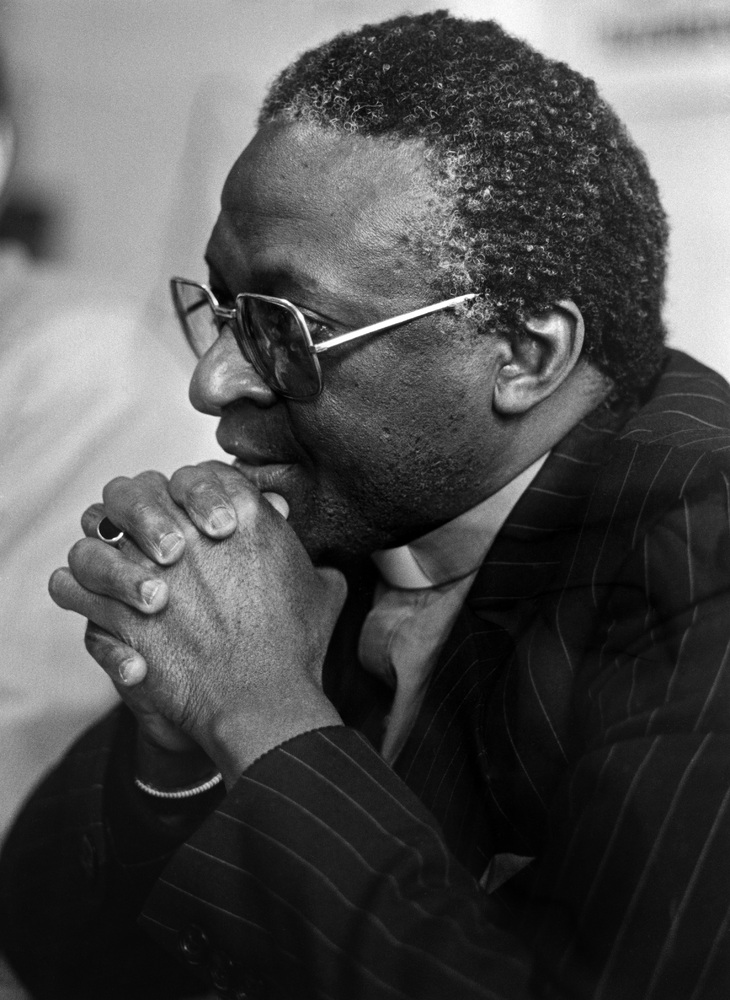

In 1983, the United Democratic Front (UDF) is formed to oppose the Tricameral legislature. The movement grows to about 3 million members from nearly 500 political, labor, youth, religious, and community groups. It adopts the ANC’s Freedom Charter, thus linking itself to the still-banned organization, and boasts Archbishop Desmond Tutu as one of its most prominent members.

Picture released on March 24, 1981 of South African activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner and Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu in Copenhagen. (AFP/Getty Images)

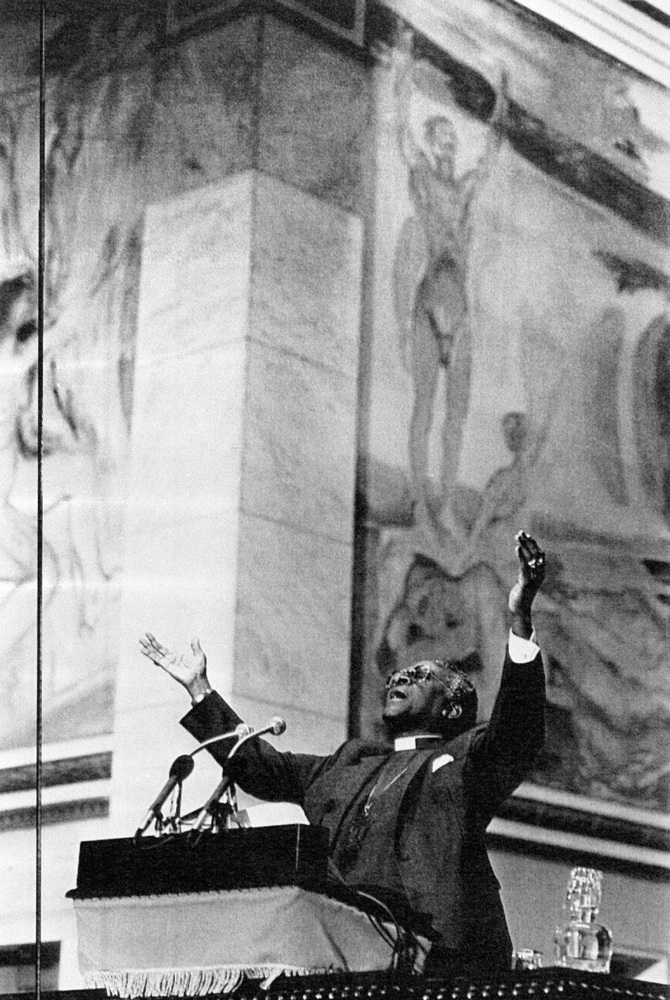

Desmond Tutu receives the 1984 Nobel Prize for Peace in recognition of his unifying role in the fight against Apartheid. The nomination sends a strong message to the Botha regime on the international status of the country’s policies.

South African activist and Anglican Archbishop and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, Desmond Tutu, gives a Nobel lecture on December 11, 1984 in the auditorium of the Oslo University, after being awarded Nobel Peace Prize the day before. (LARS GRONSETH/AFP/Getty Images)

In 1985, South Africa’s government attempts a nationwide crackdown on the growing revolution, declaring a State of Emergency and deploying troops to African townships. 18 political organizations are banned while tens of thousands of protesters are detained.

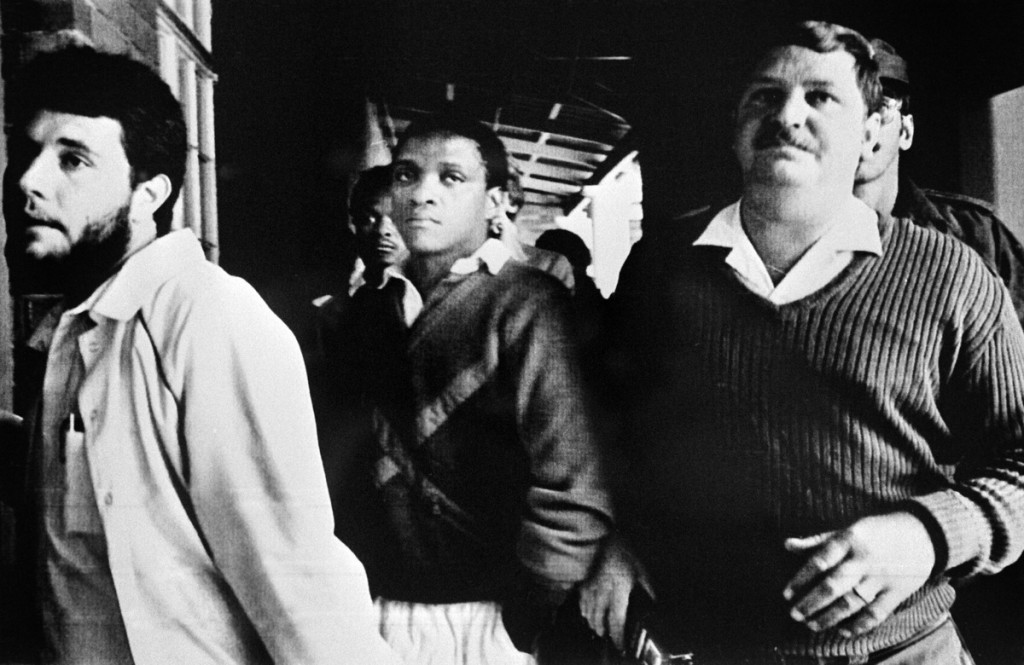

Trevor Tutu, son of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, is led from the Soweto court, on August 26, 1985, after being arrested under South Africa’s state-of-emergency regulations after he disrupted a court hearing for dozens of black schoolchildren detained by police for boycotting classes. (WENDY SUE LAMM/AFP/Getty Images)

In 1986, the United States and the United Kingdom place economic sanctions on South Africa. The national economy takes a significant hit.

In response, the South African government begins to ease its enforcement of petty Apartheid, rolling back the pass laws’ restrictions on black access to public space.

15th October 1985: Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi (1944-1991) with Neil Kinnock and Denis Healey on an official visit to London to discuss Britain’s attitude to sanctions against South Africa. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

In September 1989, F. W. de Klerk is elected president, replacing an ill Botha. Known for his pragmatic approach to reform, de Klerk repeals the Population Registration Act and eliminates most of the legal basis for Apartheid. In addition, he lifts the ban on the ANC and frees many political prisoners.

National Party leader Frederik Willem de Klerk (L) sworn in as acting State President on August 15, 1989 by the country’s highest ranking judge, chief justice Michael Corbett (R). Frederik de Klerk was elected after the resignation of P. W. Botha. (STRINGER/AFP/Getty Images)

On February 11, 1990, Mandela is freed from prison after 27 years in custody. He becomes president of the ANC in 1991.

South African National Congress (ANC) President Nelson Mandela (c) and his then-wife Winnie raise their fists 11 February 1990 in Paarl to salute the cheering crowd upon Mandela’s release from Victor Verster prison. (ALEXANDER JOE/AFP/Getty Images)

In 1991, following the final repeal of all remaining Apartheid laws and the lifting of international sanctions, multi-party negotiations begin in a push to move South Africa toward a multi-racial democracy. Despite the ongoing threat of political violence by both Afrikaner extremists and Zulu nationalists to derail the talks, de Klerk and Mandela reach a Record of Understanding in 1992 on the need for a democratically elected body to form the new constitution.

African National Congress President Nelson Mandela (R) shakes hands with South Africa’s President Frederik W. de Klerk (C) as South African Foreign Minister Pik Botha (L) looks on, 15 May 1992 in Johannesburg, after the first day of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). (TREVOR SAMSON/AFP/Getty Images)

Three centuries of white rule in South Africa come to an end in December 1993, when parliament approves an interim constitution that will grant black majority rule for the first time since the country was colonized.

ANC Secretary General Cyril Ramaphosa (L) chats with Nelson Mandela after arrival at the World Trade Center, in Kempton Park 18 November 1993, where political leaders formally endorsed a constitutional blueprint that will end 300 years of white minority rule. (WALTER DHLADHLA/AFP/Getty Images)

Nelson Mandela is elected president of South Africa on May 10, 1994. He is the country’s first black president.

South African President Nelson Mandela stands at attention as the national anthem is played during his inauguration 10 May 1994 at the Union Buildings in Pretoria. (WALTER DHLADHLA/AFP/Getty Images)

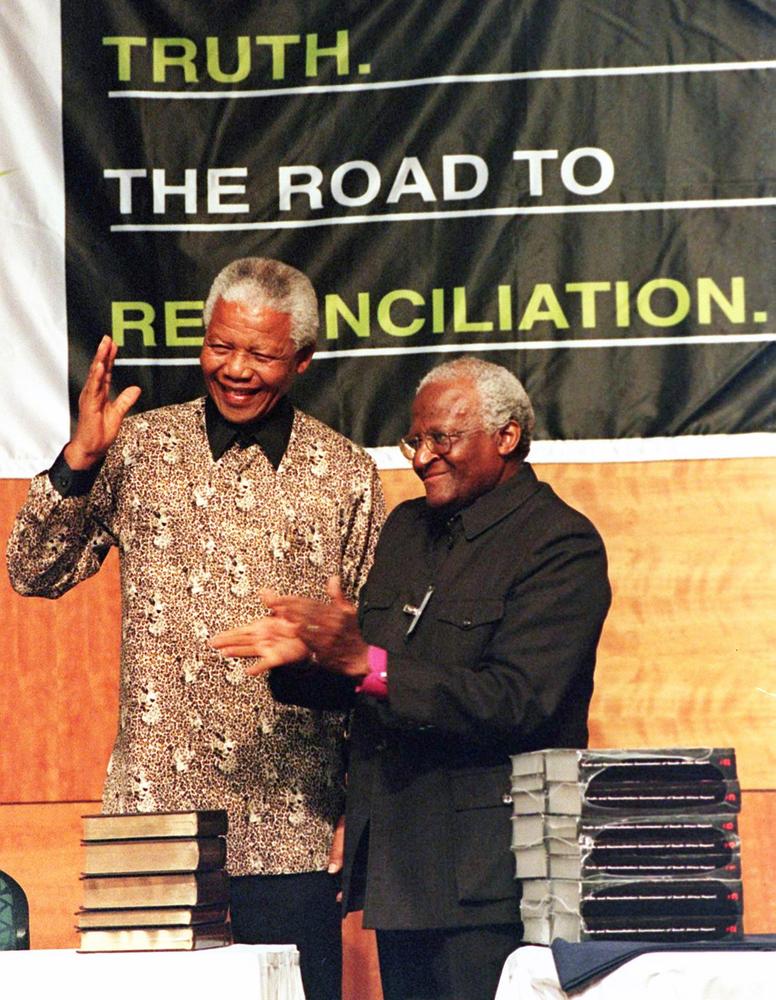

In 1995, Desmond Tutu leads the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in gathering information and data on the human rights violations of the Apartheid era. In 1998, the TRC brands Apartheid as a crime against humanity and makes detailed recommendations for financial, symbolic, and community reparations to the victims of the era.

South African President Nelson Mandela (L) with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, acknowledges applause after he received a five volumes of Truth and Reconciliation Commission final report from Archbishop Tutu, in Pretoria 29 October. (WALTER DHLADHLA/AFP/Getty Images)

Originally published by Huffington Post Quebec on May 20, 2014. You may visit the original article here.