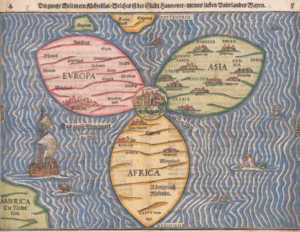

Israel, known to most non-Jews as the Holy Land, takes up about one-tenth of one percent of the world’ real estate, and has been the object of fascination and preoccupation long before Google Maps. In one of my introductory courses to Jerusalem and the Land of Israel, I show students a 16th century leaflet made by German Protestant pastor, Heinrich Bunting, titled “The World in a Cloverleaf.”

Bunting’s rendition of the world spotlights a foundational concept: that maps tell stories and reveal political and/or ideological attitudes. What is the story that Bunting wanted to tell in his symbolic “The World as a Cloverleaf?” Certainly, that the center of the world is found in Jerusalem that functions as a juncture to three major continents: Africa, Asia and Europe. Of course, for Bunting, a devout Christian, the three clovers symbolize the Holy Trinity. Nevertheless, it is an important entry-point for educators who teach about Israel: to demonstrate that Israel is not only figuratively important but sits at the center of world civilization. It has captured the world’s imagination, sometimes taking the form of fascination and at other times, contempt in the form of antisemitism.

We often rely on maps to situate a territory in students’ minds, point out important landmarks, geographic regions, or show borders. It is the last of these, borders, that is the subject of this flashpoint. Seldom do students examine a map and wonder about the legitimacy or origins of a country’s borders. It must have been this way for ages; or as one student remarked, “it just is.”

In the field of Israel Studies and among Israel advocates, the year 1947 is sanctified as the year when Israel gained world recognition and legal legitimacy. Pointing to the significance of U.N. Resolution 181, or as Israeli-American philosopher and computer scientist Judea Pearl calls it “the encounter between the Jewish people and history,” November 29, 1947, remains a hallmark of Israel education. No one can deny that 181 was both historic and significant. But its mythology has contributed to the Jewish people’s recurrent need for external recognition and reinforced a flawed timeline in modern-day Israel’s steps toward sovereignty.

To fully appreciate both the protean nature of borders, international law, and most importantly, depart from scrutinizing Israel’s legitimacy, we must reorient ourselves to the end of the First World War, to what I call the collapse of empires and subsequent birth of nation states. And more precisely, to the San Remo Conference that took place in Italy on April 19, 1920. At the conference, the newly formed League of Nations deliberated for seven days, laying out the foundation for the creation of twenty-two Arab countries and the creation of one Jewish State.

The setting of WWI centered predominantly around Eastern Europe, with the Middle East far off at stage left. Little did the Allied Powers know that decisions made in San Remo surrounding the fate of the Levant would find themselves the center of what we now call the Middle East conflict, namely the conflict between the one Jewish state and the many Arab surrounding states. On the agenda in San Remo was the British Mandate for Palestine, a territory the British won from the Ottomans, along with the British Mandate for Mesopotamia, which would become Iraq.

In attendance were Great Britain, France, Japan, Italy, with America as a neutral observer. There, the Balfour Declaration, which by itself is a letter that carries zero legal weight, was ratified, thereby transforming it from a letter of intent “into a legally-binding foundational document under international law.” Declaring that the Supreme Council should “settle as soon as possible the question of Asia Minor” (8), the San Remo conference document points to the necessity to “appoint of the mandatory Powers… and the fixation of the boundaries of the mandate countries.” From the outset, therefore, it was obvious that the Council was embarking on new terrain and that the daunting task of drawing borders would ensue. This is key and often missing from education on Israel and the Middle East. The borders we currently trace around say Iraq, Syria, Jordan were fashioned by the likes of an M. Berthelot, President of the French Council, or the Earl Curzon of Kedleston, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs of Great Britain. Human beings with lofty titles, setting out to draft international law, were the makers of today’s independent twenty-plus countries that came to be after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Russian Empire. It takes a while, I tell my students, to full appreciate the totality of this seismic shift in geography and political power.

In regard to Syria, the Council consulted the terms agreed upon at the Treaty of Peace with Turkey months earlier, as well as the Sykes Picot line (The Sykes-Picot Agreement provided an Anglo-French undertaking “to recognize and protect an independent Arab State or a Confederation of Arab States… under the suzerainty of an Arab chief” that would be established on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire). Mr. Lloyd George of Great Britain insisted that the ancient boundaries of Dan and Beersheba belong to Palestine. After days of considerations, days that examined ancient maps and verbal promises, it was agreed that as regards the region of Palestine, as long as that mandatory Power would “not involved the surrender of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” the Allied Powers were in “favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” (927). Likewise, it was agreed upon that the mandates for Syria and Mesopotamia shall be “recognized as independent States.”

And, if we are to zoom out from Israel and examine, instead the boundaries of the Mandate for Mesopotamia, which would, in 1931 become the independent Arab state of Iraq, or Transjordan which would become an independent Arab state of Jordan in 1923, we begin to fully grasp the perfunctory nature of creating borders, and with that, sovereign nation-states.

The Mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia were both submitted for approval of the League of Nations in December of 1920. The proposed territory of Mesopotamia became the independent Kingdom of Iraq in 1931-1932. It is difficult to say which decisions governed the British in their decision to outline the borders of a future Iraq, especially given the fact that the Kurds, a people most similar to the Jews in that they, unlike modern-day Iraqis, truly are indigenous to the Mesopotamian plains, were given little to no consideration.

But who dares to ask what about Iraq’s legitimacy—its right to exist. Especially given that in a 1932 memorandum, King Faisal, himself born in Mecca wrote: “In this regard and with sadness, I have to say that it is my belief that there is no Iraqi people inside Iraq. There are only diverse groups with no patriotic sentiments. They are filled with superstitions and false religious traditions. There are no common grounds between them… It is our responsibility to form out of this mass one people that would then guide, train and educate.” What’s more, in less than a century, Iraq has had nine flags and five national anthems. What this fractious historic process reveals is the fragility of a nation-state that is not rooted in indigeneity. Within a short century, Iraq’s identity has been captured by socialists, communists, capitalists, theocratic, and radical Islamists. And today, the government is scrambling to defeat the militants of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL. All this is to say that King Faisal’s objective to “form out of this mass” a nation, has been, too wit, a catastrophe.

The same, of course, can be said of Jordan, a country created “by codicil in the mandate for Palestine” in 1922. Aware of the promises made to the Arabs to gain political sovereignty in exchange for helping to fight the Ottomans during the First World War, the British turned their attention to the Hashemite Kingdom, a royal family who had come from the Arabian Peninsula. To simplify, the birth of Jordan is a “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch your back” condition. The Arabs who had revolted in 1916 against the Ottomans and who were promised political independence, were awarded sovereignty, but not on the status of indigeneity. Indeed, the only country that was awarded independence based on indigenous status was the Jewish state. Chief among the decisions to transfer the British Mandate of Palestine to the Jews were ancient maps of the Kingdom of Israel and other archeological evidence of Jewish sovereignty that dated back to the First and Second Temples.

I often ask students what gives any country the right to exist. No one asks France, Turkey, or Poland to produce their birth certificate documents; moreover, no one asks what gives them the right to exist. As Eugene Kontorovich writes, “countries do not require or receive permission for their establishment. They do so either by agreement with the prior sovereign or, more commonly, by success in a contest of arms.” Or as a recent refugee from Ukraine reminds me, “nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons sure do help ensure a country’s existence.” This, then, brings us to a position that is seldom used in polite society today: might over right, or the success of contest in an armed struggle. Israel’s successful defensive war in 1948 led to the legitimacy of Israel because, bluntly put, they “won” the war.

Here’s the hard truth: those who require Israel, and Israel only, to provide proof of its legitimacy are partaking in a delegitimization campaign. And what’s more, Israel educators who compel their students to recite the indigenous, legal, historic, and divine claims of the Jewish people to the land of Israel are, for better or for worse, complicit in this anti-Jewish crusade. They do so, of course, with the best intentions: to prepare and equip Jewish youth to be able to articulate Israel’s right to exist.

But I invite educators to take pedagogical risks: to rethink their learning objectives. In doing so, an entire cosmos of educational approaches surface. Below is one such approach which asks students to trace the borders of a rendition of the mandate system:

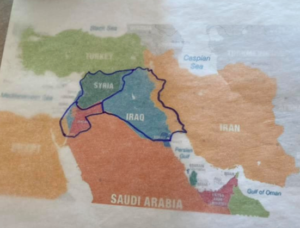

Image 1 Image 2

Image 3

In the exercise above, I ask students to trace the borders of the map from Image 1. These are, of course, borders of British and French mandates from 1920. At the end of the lesson, I give to students a second map, see Image 2, a contemporary one with countries and borders. For the final step of the exercise, I ask students to overlay their tracing paper on top of the contemporary map and make observations. Most often, students remark that the only country that did not retain its borders from the original mandate system is Israel, as seventy-seven percent of the British Mandate for Palestine was given to Transjordan. All in all, they are in awe at the idea that many countries are quite young and border quite fragile, and most certainly, are completely prepared to address the folly wrought in the question, “who gave Britain the permission to gift Palestine to the Jews?” To this, they say, “you mean the same Britain that gifted Iraq to the Arabs, Lebanon to the Arabs, or Jordan to the Arabs…?”

Sources:

Ahren, R. (2020), “On centenary, San Remo Conference hailed as ‘seminal moment’ in Zionist History,” Times of Israel.

Karsh, E. “The San Remo Conference at 100 Years,” in the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategies Studies, Bar-Ilan University.

Grief, H. (2020), The Legal Foundations and Borders of Israel Under International Law, Mazo Publishers.

Kontorovich, E. “The Significance of San Remo,” in Mosaic Magazine, Feb. 15, 2021.

Kramer, M. “Did the San Remo Conference Advance or Undermine the Prospects for a Jewish State?” in Mosaic Magazine, Dec. 1, 2020.

“Minutes of Palestine Meeting of the Supreme Council of the Allied Power held in San Remo,” April 24, 1920, Jewish Virtual Library.

Avalon Project, “The Palestine Mandate,” July 24, 1992, Preamble.

Laqueur, W. and Schueftan, D. (2016) The Israel-Arab Reader: A Documentary History of the Middle East Conflict: Eighth Revised and Updated Edition, Penguin Books.

Luay al-Khatteeb, “Iraq’s New Independence: Reclaiming a Nation’s Lost Identity,” NewLines Institute for Strategy and Policy (1920).

To submit an article to ISGAP Flashpoint, paste it into the email body (no attachments). Include a headline, byline (author/s name), and a short bio (max. 250 words) at the end. Attach a high-quality headshot. Send submissions to [email protected].