A Re-Discovery of the SS-Leader’s Anti-Balfour Cable to the Grand Mufti

In April the National Israeli Library blogged Himmler’s re-discovered telegram to the grand mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husaini. Contrary to the comment there that Nazi Germany did not declare its help for the Arab independence, I argue, it did. This cable further recognized the movement of the Mufti, who lived from 1941 to 1945 in Berlin. He realized with the Axis powers his main goals against the Jews and Allies, also in the Mideast. The thesis that his only success was preventing “a few cases of Jews departing Europe for Palestine” denies his own admissions and ideological roles. He described the fate of Jews who were forced to remain in Europe after his protests, especially of Hungarian Jews. I will shed historical light on this cable.

On the 26th anniversary of the Balfour-Declaration, Heinrich Himmler sent his best wishes for success to the Mufti’s related “protest meeting” that took place in Berlin’s city. Of course, such public support for al-Husaini would have been impossible without Hitler’s prior consent. It would come swiftly, for he and the Mufti had agreed on a 1941 anti-Jewish pact of genocide.

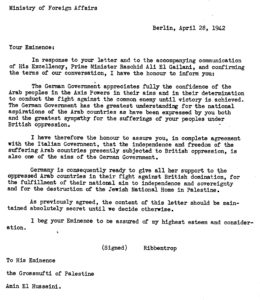

Pic. 1: Himmler’s anti-Balfour Declaration Cable as sent to al-Husaini on November 2, 1943

To the Grand Mufti Amin al-Husaini,

the National-Socialist Movement of the Greater German Reich has since its advent upheld the flag of its fight against world Jewry. Thus, it always closely watched the fight of the freedom-loving Arabs, above all in Palestine, against the Jewish intruders. The recognition of this enemy and the joint struggle against it are the firm base of the natural alliance bet-ween the National-Socialist Greater Ger-many and the freedom-loving Muslims of the whole world. In this spirit, I am con-veying to you, on the anniversary of the wretched Balfour Declaration, my hear-tiest greetings and wishes for the lucky realization of your struggle until the certain final victory.

Reichsführer-SS, Heinrich Himmler (click on picture to enlarge)

On that November 2, 1943 the SS leader cabled this 100-word-telegram to his guest’s “anti-Balfour Declaration” meeting to protest the 1917 letter written by the British foreign secretary Arthur J. Balfour to Jews that favored a Jewish national home in Palestine.

Supporting and instigating Mideasterners who turned against this “imperialist plot,” rather a Jewish self-liberation, Himmler assured al-Husaini the official sympathy of the Nazi movement with the freedom-loving Arabs, above all in Palestine, against the world Jewry. In reality, it was always a two-way-street, for the Mideast also shaped young Nazis. Many of them fought there as officers on the side of the Ottomans and advanced three decades later to commanders in World War Two. Hitler’s press, on the other hand, idolized war minister Enver Pasha and later Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s resistance against the Allies and results of World War One.

Moreover, Himmler, the third strong man, after Hitler and air force Chief Hermann Göring, named all Jews their joint enemy. He pointed at two parallel movements converging in Europe and the Mideast against those “common foes.” To the latter belonged London, and since 1922 also Washington DC and the League of Nations with the Mandated Area, which agreed to Lord Balfour’s promise of Palestine for a Jewish national home.

The protest meeting was in Göring’s Luftwaffe Ministry, House of the Aviators. So al-Husaini was well connected to the top three men of Nazism. Why Göring? In February 1943 the Mufti invested his war chest with foreign money, $920,000, in shares of seven big German companies. After Hitler’s consent, Göring managed it as trustee. Had Berlin won the war, al-Husaini would have been a rich leader of a Greater Arab Empire based on Nazi lines.

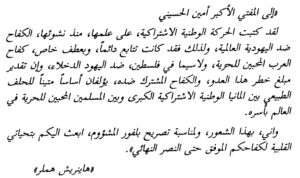

Pic. 2: Al-Husaini, al-Kailani (click on picture to enlarge)

The Mufti was not the only Arab guest in the Luftwaffe chief’s office near Brandenburg Gate. Listening to his speech was Ali al-Kailani, Iraq’s ex-premier who led the failed anti-British coup in Iraq. There, in mid-1941 he and the Mufti initiated the al-Farhud pogrom as a “model to treat the Jews.” Hitler ordered help and used it as a diversion of his ensuing war against Russia.

Himmler said in his cable that “their joint fight against the Jewish intruders” rests on the natural alliance of Greater Germany and Islamic areas. He treated al-Husaini as the Palestinian, Arab and Muslim leader. The Nazi saw the ideologies as well: German National-Socialism and Palestinian National Islamism. But this contradicted a 1917 theory of Islamism calling for just one global Muslim Brotherhood not only for one area like Palestine, but for all Islamic regions.

Pic. 3: Foreign Minster Joachim von Ribbentrop to al-Husaini in a top secret letter on behalf of the Axis powers in Berlin and Rome: Yes to the Arab independence and yes the destruction of a Jewish home in Palestine (Click on picture to enlarge)

Al-Husaini got what he wished for: an Axis broadcast on the Arab independence; the halt of Jewish emigration to the Mideast by the Nazis; and a secret 1942 letter between Berlin, Rome, al-Kailani and him to agree to liquidate a Jewish home in Palestine. Now he wanted public recognition of the “natural alliance” between Nazism and Islamism. Since 1937 he forwarded four key drafts. Paragraph seven always stayed the same: a Jewish home is illegal. Even when in May of 1943 the Axis had been driven out of the Mideast, he asked them to destroy the Jewish home.

In his cable Himmler reminded the Mufti of a “natural alliance.” Al-Husaini knew this term from WWI. It was often used as he was a young Ottoman officer posted in areas of Armenian deportations. But in 1943 the magnitude of the Nazi debacle at Stalingrad, a loss of 110,000, men was sinking in. Himmler got desperate to recruit Muslim soldiers with al-Husaini’s help: in Bosnia – Berlin praised him as a recruiter of 20,000 SS men – and Russian Muslim POW’s.

The Mufti met Himmler on July 4, 1943 at his field quarters. They spent a day with SS men, all known Jew-hunters. Two years prior, the local Jews had been killed by SS-commandos. Hitler tasked Himmler to steer the shooting of Jewish civilians “as partisans” in occupied Eastern Europe and to round others up for labor and death camps. Al-Husaini praised his meeting with Himmler thereafter as a solid base of mutual trust.

On that summer day, Himmler told the Mufti of having so far killed three million Jews. He confided to him other top secrets. The German nuclear research advanced: In three years, Berlin will have an atomic weapon that would secure the “final victory.” The same word on a “final victory” was in Himmler’s cable modified by “certain,” perhaps betraying some uncertainty.

A year earlier, the Axis elevated al-Husaini, not al-Kailani, to the leader of a future Greater Arab Empire. In turn, the Mufti soon informed Berlin about the Allied landing in North Africa. But Hitler didn’t believe it. Many of the Mufti’s ideas remained idle: Arab-Islamic troops posted between Tunis and Cairo, an Islamic Department in Berlin’s Foreign Office, a joint trip to the Arab West with spy chief Wilhelm Canaris, to mobilize “French Arabs” as soldiers and to bomb a 1943 Zionist meeting on the Balfour day in Jerusalem. But Göring had no airplanes to spare.

In 1943, as Nazis left the Mideast and retreated in Europe, the Mufti sent 60 men to be trained as paratroopers to Den Haag’s SS “sabotage school.” He called them his “troop kernel” for the war against Palestine’s Jews. He visited his “Dutch commandos” in August. In turn, Himmler rewarded him with that anti-Balfour telegram, given to each participant with the Mufti’s speech.

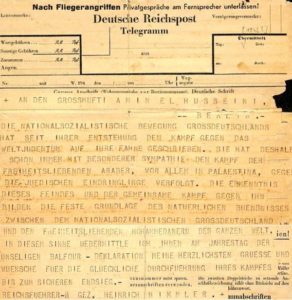

Pic. 4: Himmler’s 1943 cable to the grand mufti al-Husaini as displayed in his 1999 memoirs (Click on picture to enlarge)

Therein he painted Jews as “cosmic evil.” He denied them ancient ties to Palestine, claimed they only use imperialists. Himmler was told about the Mufti’s speech. So at the year’s end Himmler’s telegram was in many hands with the code “final victory” (this is missing in the Library’s English translation) giving a public to al-Husaini: he had his back. Later, it was edited often, also since 1947 in America and by the Mufti himself in Arab journals and his memoirs.

In hindsight, al-Husaini recalled that the Ottomans, allied with the Kaiser, talked to Jewish delegates on a Jewish home in Palestine. Of the Three Pashas Enver, Cemal and Talat, the latter took over. After half a year of talks, in mid-1918, Talat issued an Ottoman Balfour Declaration: Istanbul’s Council of Ministers lifted all restrictions for Jewish emigration to and colonization of Palestine. They welcomed a religious and national center for Jews as equals among others.

Al-Husaini read that declaration in Turkish. It looked like the Balfour text, he remembered. Published in September of 1918, it went down with the crumbling empires. From a view point in German-Mideastern history, the Pashas hoped that Jews would also bring development and taxes, a modern turn to a commonwealth. The Ottomans as the last predominant Muslim government found a fair way on their tradition of negotiations, closer to historic realities, that the Mufti had regularly rejected. He said no to Jewish historical ties to Palestine and British suggestions in favor of a Palestinian home. Instead, he put all his eggs into Hitler’s basket, and lost with him.

To submit an article to ISGAP Flashpoint, paste it into the email body (no attachments). Include a headline, byline (author/s name), and a short bio (max. 250 words) at the end. Attach a high-quality headshot. Send submissions to [email protected].